Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In The Time Shelter, the Bulgarian novelist Georgy Gospodinov tells the story of Gaustin, an enigmatic flâneur who opens a “clinic of the past” in Zurich to try to cure people of Alzheimer. In the clinic he reproduces different decades of the 20th century to help the ill return to a moment of plenitude in which their memory had not yet deteriorated. It was an experiment that, as the protagonist tells us: “…consisted of creating a protected past or a ‘protected time’. A refuge of time, a chrono-refuge. He wanted to open up a window in time and let patients live there, with their families, as well” (Gospodínov 2022: 133).

Without a doubt, this “chrono-refuge” is one of the best figures of nostalgia: a return to the safe and complete moment in which the patient’s world has not yet collapsed. It is curious that in the novel nostalgia functions in its original clinical setting, like the illness the medical student Johannes Hofer described when he coined the term in 1688: “the sad mood caused by the longing to return to one’s native homeland” (Boym 2015:25). This “mood” over time went beyond the limits of the clinical to become a complex cultural emotion that ended up crystallizing as one of the fundamental responses to modernity: “a defense mechanism in an age of accelerated rhythm of life and historical upheaval” (Boym 2015: 15).

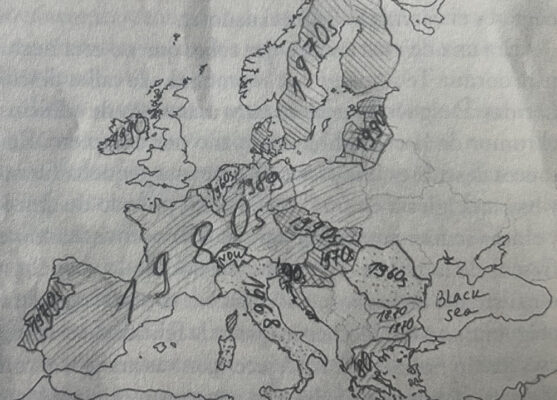

In The Time Shelter, nostalgia also leaves beyond the medical field and spreads to all corners of an unstable Europe that longs for security, and the chrono-refuge becomes a political option. “Since a Europe of the future is no longer possible, we are going to choose the Europe of the past. It’s simple, when you have no future, you vote for the past” (Gospodínov 2022: 166). This is the argument for the start of a great European referendum in which each country chooses a decade or a happy time to which to return. In Spain, the 1980s is chosen.

#

I am convinced that Svetlana Boym would have loved Gospodinov’s novel. Few books better embody the sense of what, in her monumental study of this emotion (Boym 2015), she calls “restorative nostalgia,” that which is based on the fiction that there was a complete and happy time in the past and that it is possible to reconstruct it, to restore it, in the present. In opposition to this desire for a recreation that emphasizes a return (nostos), Boym suggests “reflective nostalgia” which prioritizes loss, pain (algia), and which is aware that this happy past can’t be recovered, in part because it is nothing more than an imaginary construction carried out in the present.

This two-faced aspect of nostalgia is what the texts we have published this July in A*Desk examine. From different places, positions and intellectual traditions, Aarón Sáez, Azahara Palomeque, Irene Martínez Marín and Ernst van Alphen have approached nostalgia in order to explore its dangers but also its transformative power.

In “Nostalgia as a Weapon,” Aarón Sáez observes the disappearance of the myth of the future and the comfort of returning to what has already been experienced, the comfort of repetition and its sometimes harmful and immobilizing uses in entertainment culture. The constant reproduction of a past that, as Irene Martínez Marín points out in “Nostalgic and Sincere,” is always contaminated and shaped by our present and by our place in the world.

This manipulative and fictionalizing present of the past is precisely what Ernst van Alphen examines in his text on the uses of nostalgia in contemporary politics: the wonderful, pure past to which extreme right-wing movements want to return and the mythical, illusory past that seeks to legitimize the genocide that is taking place in Gaza. Only a reflective, critical and non-restorative use of memory can create a possible future for Israel and Palestine.

The destruction of the home and the sense of despair that comes with it is a fundamental characteristic of armed conflicts, but it is also one of the biggest effects on the land by extractive capitalism. Glenn Albrecht calls this despair for a home that is threatened “solastalgia” (2005), a term constructed from the Greek root of “pain” (algos) and the Latin root of “comfort” (solacium). This is the emotion that Azahara Palomeque explores in “Ithaca in Danger: From Nostalgia to Solastalgia,” the unease and helplessness we experience when what we consider home has begun to become extinct and “the earth disappears under our feet.”

#

In her last work, published after her premature death in 2015, Svetlana Boym emphasized the future meaning of nostalgia and dedicated several pages to exploring the concept of “prospective nostalgia” (which she had already outlined in her classic book), a non-paralyzing nostalgia that emphasizes the discomfort not for what was lost but for what could not be conquered. I like to call it “productive nostalgia” to emphasize its active condition, its ability to act, to produce and to create something that moves us forward. It is a nostalgia that takes its strength not from a past arcadia but from a future that never came, one of the truncated paths of history of that which did not occur.

Here, without a doubt, Benjamin’s ideas resonate: not the longing for the well-being of the past but for the dream that was not achieved, the revolutionary energy of the possible. In this sense, prospective or productive nostalgia will always be based on a lack, a hole, and never on a fictitious plenitude to which to return.

This true power of nostalgia can be harnessed in order to transform the present and move forward, but also to stop losing. Loss must be conjugated into the present. It is not what was lost or what will be lost but what is lost at every moment. The real catastrophe is not what is yet to come but that which is already here. Benjamin sensed this in his Arcades Project: “that this ‘continues happening’ is the catastrophe” (2005: 476). If nostalgia works as a pain that wakes us up, that stings us and manages to mobilize us in the end, then let’s welcome that prick, that discomfort, that lost gaze on the horizon that precedes an uprising.

References

Albrecht, Glenn. 2005. «Solastalgia. A New Concept in Health and Identity.» Philosophy Activism Nature (3): 41-55.

Benjamin, Walter. 2005. Libro de los Pasajes. Madrid: Akal.

Boym, Svetlana. 2015. El futuro de la nostalgia. Madrid: Antonio Machado.

—. 2017. The Off-Modern. Londres: Bloomsbury.

Gospodínov, Gueorgui. 2022. Las tempestálidas. Logroño: Fulgencio Pimentel.

(Cover image: “Map of Europe after the temporal referendum.” Gueorgui Gospodínov, Las tempestálidas, 2022.)

Miguel Ángel Hernández (Murcia, 1977) is a writer, art critic and professor of Art History at the University of Murcia. His essays on art and visual culture include “La so(m)bra de lo real” (Holobionte, 2021), “El arte a contratiempo: historia, obsolescencia, estéticas migratorias” (Akal, 2020), “El don de la siesta” (Anagrama, 2020) or “Materializar el pasado” (Micromegas, 2012). He is also the author of four novels published by Anagrama: “Intento de escapada” (2013), “El instante de peligro (2015)”, “El dolor de los demás” (2018) and “Anoxia” (2023). He regularly collaborates with the curatorial group 1er Escalón.

www.mahernandez.es

Retrat © E. Martínez Bueso

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)