Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

History sediments in bodies and cities like palimpsests – scrolls, pages, or tablets that are used again and again, earlier layers of writing are scraped away and new text is superimposed. But the past rarely stays where we think it belongs, palimpsests are reused and altered yet may bear traces of earlier lives. History is an ongoing process that loops through itself, again and again, making a mess of past, present, and future. The past is not locked away in a vault, and anyway even locked doors can’t stay closed forever but, like bodies, will eventually decay, transform, collapse.

CALLE LA RONDA, QUITO

I knew it was going to rain soon because it rained every afternoon. “Lluvia,” I repeated in my head, trying to force my brain to think in Spanish and to remember the difference between lluvia, rain, and llorar, to cry. He was wearing a knit white sweater, to him it was always sweater weather, and in mid-thought… “Pero, no estamos tristes” he said, then took a sip of his canelazo, lifted his arms, and made a partying motion. Reflexively my body tensed, my brain blanked. I couldn’t remember whether or not I was sad.

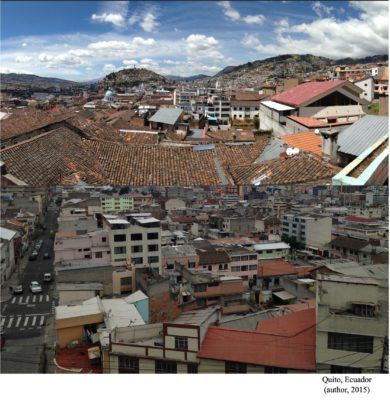

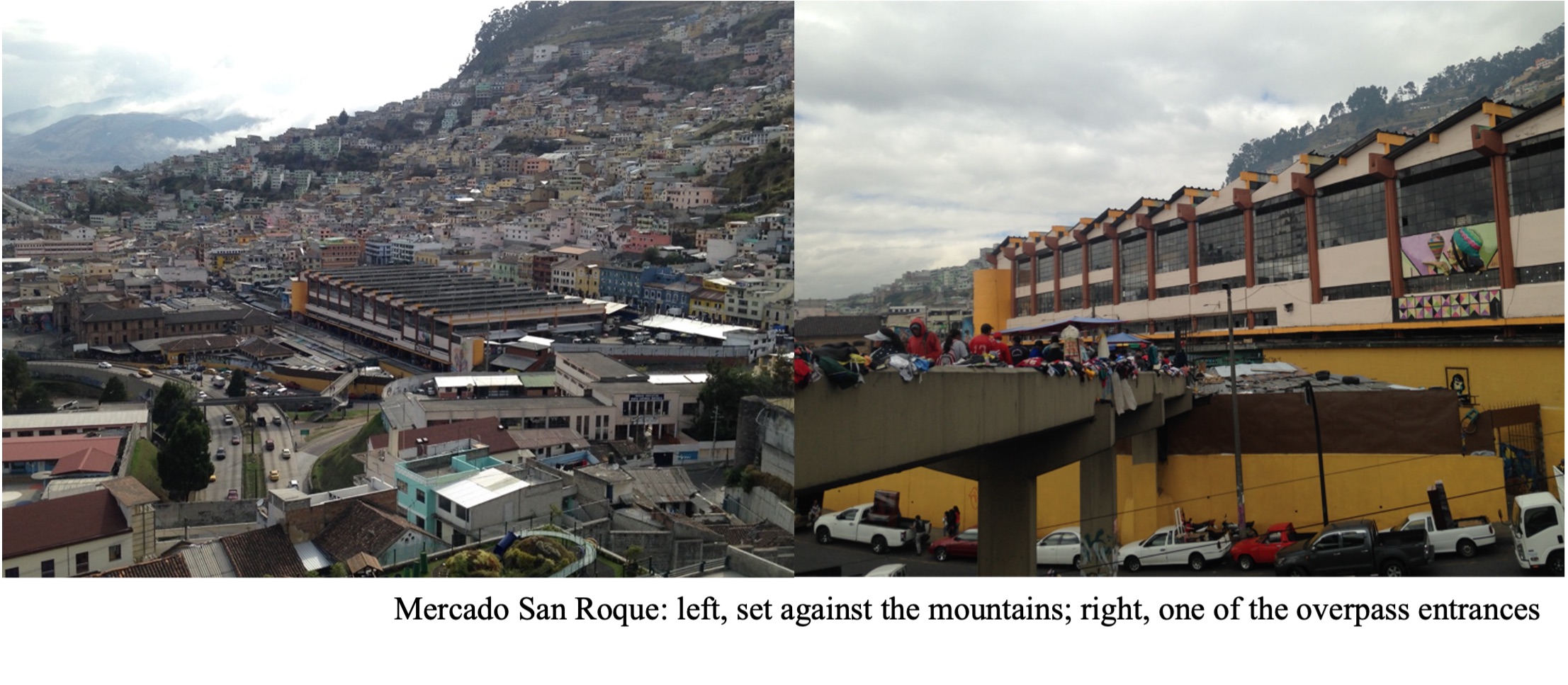

We were sitting in a hole-in-the-wall restaurant on Calle La Ronda, the only one open. He had wanted to show me a museum depicting Quito’s history with wax figures, but it was Sunday and the museums, along with nearly everything else, were closed. In front of the restaurant, meat was cooking on an open grill and a sign advertised $0.75 canelazos, a warm concoction of aguardiente, fruit juice, and spices. From where we were sitting, I glanced uphill to Mercado San Roque, a large wholesale and retail food market. My master’s thesis was about the various flows of value that move through the market, a project I hoped would demonstrate that urban and rural spheres were not actually distinct but blurred and blended. However, immersion in fieldwork had begun to break down boundaries far more personal than the abstract urban or rural. I found myself having difficulty determining whether my body and mind were moving through the past or the present, reality or fantasy.

But instead of working on my thesis, I was ordering canelazos de naranjilla with this sweater-wearing boy. I had put out a call through my Grindr profile for artists, for punks, for the broken people, the sad people. He liked that. He wasn’t sad though, he was a dancer, full of energy and kindness. He teased me about my Spanish, but he was patient and liked to wink at me while I haphazardly slurred words and muddled verb tenses. We passed time together in an amalgam, a physical and mental space of relation and confusion between English and Spanish, North America and South America.

But instead of working on my thesis, I was ordering canelazos de naranjilla with this sweater-wearing boy. I had put out a call through my Grindr profile for artists, for punks, for the broken people, the sad people. He liked that. He wasn’t sad though, he was a dancer, full of energy and kindness. He teased me about my Spanish, but he was patient and liked to wink at me while I haphazardly slurred words and muddled verb tenses. We passed time together in an amalgam, a physical and mental space of relation and confusion between English and Spanish, North America and South America.

PARQUE ITCHIMBÍA, QUITO

I couldn’t remember whether or not I was sad. We were sitting in a hill-top park with a view of the whole city center. The Centro Histórico contained many worlds, there were hostels, luxury hotels, spacious apartments for the emerging middle class, and subdivided flats where two or three migrant manual laborers shared a room with only one bathroom per floor. There were wooden-walled cafes with marble tables that served espresso and wooden-tabled restaurants with peeling wallpaper that served comida típica and only had instant coffee. Gringo tourists, latino tourists, Ecuadorian mestizos, and indigenous migrants all moved through the streets; the scales, speeds, and purposes of their lives coalescing and contradicting. These worlds, separate as they seemed, violently collapse in on each other, creating a chaotic imbroglio of indigenous, colonial, and neoliberal histories.

My head resting in his lap, I asked banal questions, “Y ¿qué es eso?” pointing from one area to the next, “Y ¿qué es eso?” He told me a story about a colonial phantasma, one of many, that had been woven into the urbanscape:

They say a ghost mother wanders Quito’s Centro Histórico neighborhood, wailing for her lost child. La Llorona was raped and impregnated while working as a maid. She drowned her newborn, the product of sin, and now haunts the streets to punish adolescents engaging in forbidden love.

NEW YORK

The first boy who raped me is on a TV show now. He has his own IMDB page. If I’m being honest, I was just looking at it and watched a trailer for a movie he was in about non-monogamous New Yorkers. It looked good.

I can hardly even remember the experience anymore. I’ve spent so much time processing and crying and ignoring and flashbacking and dreaming and fantasizing and fucking about it that what actually happened and what layers I’ve added on have baked together. I don’t cry about it anymore, except very infrequently when I’m drunk. I don’t really fuck about it anymore – although that proved a useful and healing practice – but I still have the rape fantasies, the desire for someone else to come along and rape the rapist out of me.

I often can’t remember when to feel joyous or depressed, I often don’t know if I’m sad. The past, the present, reality, fantasy, pain, and ecstasy have become convoluted, messy, and inseparable.

CENTRO HISTÓRICO, QUITO

The Centro Histórico was declared a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1978. UNESCO’s website reads, “Quito, the capital of Ecuador, was founded in the 16th century on the ruins of an Inca city.” The ruins of an Inca city. The violent and exploitative process of colonization that ruined the city is conveniently absent, left out of the official cultural heritage while paradoxically absolutely necessary to it. The Inca and the indigenous people before them evanesce behind an architectural history in which the built form of the city is seemingly sanitized of its inhabitants.

To the east of the Centro Histórico, barrio La Libertad climbs out of the valley, up the Andean slopes. Pastel pink, yellow, and blue houses line the hairpin curved road, thinning with each ascending topographic line. On one of the neighborhood’s high points, Cima de la Libertad, sits Museo Templo de la Patria, a museum commemorating a battle for independence from the Spanish Crown. On top of the museum’s building, a large vibrant mural depicts a pair of brown hands breaking free from their chains, in the background two chromatic indigenous men hold weapons while two dull mestizo men hold plume and paper. That the indigenous people working the feudal hacienda system were largely unaware of the formation of the independent Ecuadorian state or that the indigenous people who did fight in the “independence” battles were coerced and manipulated appears unimportant.

This is how the palimpsest of history works – both materially and socially – the past is rarely completely erased, just distorted and either glorified or ignored. The past, the present, reality, fantasy, pain, and liberation are collapsed into two dimensions, stylized to be colorful and palatable

CALLE LA RONDA, QUITO

I couldn’t remember whether or not I was sad. He was trying to remember the English word for salchicha. When he couldn’t remember a word in English or Spanish he would slightly squint his eyes and lightly tap the tip of his tongue. If I remembered it first he would gingerly lick his fingertip and motion towards my forehead while making a sizzle sound, “ttssss.” Finally, he looked up salchicha on his phone and when he found it, he tried to pronounce the English word. As he spoke in English, which I rarely heard, I cocked my head to the side and made my own squinty, thinking eyes. He said it again… “Sausage!” I blurted too loudly in the excitement of recognition. “Ttssss,” he hissed gently, it sounded like rain.

When the sky weeps here sometimes it is light and refreshing but sometimes there are great downpours, aguaceros that saturate even the thick stone walls of the colonial churches. Either way the tears are usually short-lived, hour-long outpourings that are simultaneously emotional and stoically geochemical.

IN BETWEEN

I’m not sure where I am. I’m choking on history. I keep gulping for oxygen and clean simplicity but my lungs are filled with humidity, pollution, and complications. When the sky rains I project my own desire for it to cleanse the earth. Instead, it seems to loosen the soil, allowing the pain to settle in deeper.

CALLE LA RONDA, QUITO

The reggaeton song that had made both of us roll our eyes when it came on ended jarringly switching to a slower ballad. “Es bueno que estamos tomando,” he said, nodding towards the speaker. “¿Por qué?” I didn’t get it. “Cuando estas triste y quieres tomar mucho escuchas esta música,” he said with a wink and then quickly added, “pero no estamos triste.” He took a sip of his canelazo, lifted his arms, and made a partying motion. Reflexively my body tensed, my brain blanked. I couldn’t remember whether or not I was sad. I took a gulp of warm canelazo, my taste buds delighted by naranjilla and clove. “No, no estamos triste,” I acquiesced and leaned across the table to distract myself with his lips.

* This text was originially written in 2015, while I was in Ecuador, and a previous version elongated has been published in Hand Job Zine, volume 2: Tears.

Tait Mandler is writer, researcher, and designer who explores urbanisation as process of imploding bodies and cities, economies and ecologies. Their current research traces the mobilisation and transformation of the sensory system through the unfolding histories and shifting geographies of food and drink production, circulation, and consumption in Amsterdam. Eclectic and interdisciplinary, their previous research and writing has examined international polar bear conservation regimes, the pleasures and productivity of drug use by queer nightlife workers in Brooklyn, and the circulation of potatoes and value through a marketplace in Ecuador.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)