Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The debate on the approval and implementation of the Statute of the Artist in Spain raises several fundamental issues concerning the role of the art worker in society. The need for the statute, its process of elaboration, the difficulties and the clashes that characterised the years before it was presented to be evaluated by the Spanish parliament reveal how the coexistence between artists and other groups of workers is different in these latitudes, a rara avisreplete with footnotes.

Mar Arza and myself, two white European female artists, regard this conversation as an exchange of points of view and of queries. It isn’t a question of praising an initiative but of highlighting the frictions, and perhaps too of presenting a general panorama of the artist in times of crises, although we ignore whether the artist is familiar with other kinds of times.

Alba: We’ve been rereading a series ofdocuments: the ‘Documento Marco del Estatuto del Artista, el Autor/Creador y el trabajador de la Cultura’, the ‘Informe de la Subcomisión para la elaboración de un Estatuto del Artista’and the ‘Documento de trabajo del Estatuto del Artista Visual’ published by theUnion of Spanish Contemporary Artists. Do you think this will become a reality and yield results? If it does, I think it will improve the lives of a very small percentage of workers, and that the problem lies in our structural, economic and cultural context, which explains how individual initiatives are discouraged by today’s regulation of self-employment. I think we should engage in a little self-criticism. When we emphasise our exceptionality as cultural workers or artists, I think we should mention as a counter-example a collective like No+Precariedad that includes doctors, taxi-drivers, chambermaids and members of many other professions with no specific filter, so familiar with precariousness, and ourselves, presumably the avant-garde of precarious workers — I don’t know whether we should be with them instead of in our particular limbo.

Mar: In our case I think there is a preceding process of preparation, definition and production that isn’t reflected anywhere, that isn’t valued or counted as work. It is precisely this underground part that supports the rest. Exceptionality only lives on the visible part of our work, i.e., exhibitions and their public relevance.

A: The earlier work would be research.

M: As regards visual artists, the preceding work would be our hours of reading and searching, management work, the time we spend in our studios or other working spaces or in relation with others, in order to identify the openings, develop and share them.

A: Of course, I can’t bill any of this work; it’s not quantifiable.

M: In other contexts, work relations and shifts are much clearer. Our case remains undefined because work is only quantified if it has economic repercussions. Yet this should somehow come to the surface, because otherwise how can we justify the silences, the intermittence? The other day at a meeting of the National Council for Culture and Arts (CoNCA, for its initials in Catalan) someone mentioned that artists didn’t face the same problems musicians face to be hired, because artists establish commercial relations issuing bills for their professional fees or for the works they sell. If you work uninterruptedly on a specific project for an art centre, an exhibition at a gallery or a retrospective in a museum, your work isn’t counted as hired work because it’s supposed to be a liberal profession and a commission. If the objective is to sell art, it may or may not have economic repercussions, so all the work or a great part of it can come to nothing. If the objective is public communication and fees have been paid, as regards billing purposes it is still a commercial relationship. Can all the time elapsed between the moment an institution commissions a project from you and right up until the exhibition is brought to a close and dismantled be considered labour relations? During that whole period you’ve been in charge of conceiving the project and addressing all the demands it involves. The initiative of the Statute of the Artist doesn’t suggest this should all be recorded, but that there be compensatory mechanisms, such as the possibility of receiving more unemployment benefit for the cessation of activity when contributions are paid by the self-employed. These mechanisms continue to reward those who already have jobs, but I’m not sure whether they help compensate other less visible kinds of work. This is the case of long-term projects that find no direct space of diffusion or repercussion. So how could the present situation be dismantled?

A: Well, the agreement between the Swedish Artists’ Association and the state in connection with the regulation of fees, for instance. How do things that appear to be intangible break? Materialising them, but how? Through money and social security benefits. Is this recognition expressed by money? There are many ways of quantifying labour. Everything that is regulated can be discriminatory, but the question is, is this useful to us? Is it what we want? I’d like to return to the question of the flexibility of precarious workers. We’ve deregulated a lot, but where has that got us? I could be an entrepreneur even if all I own is a car or a house; I can be a Uber driver, an Airbnb host. We’ve deregulated everything and have reached the imminent dismantling of the welfare state. I feel artists have remained in a stronghold where we still think in terms of possibilities, of emancipation; we think from a discursive privilege in which we remain on the margins of a terrifying material reality as regards ecology, and this breaks when we support, however slightly, initiatives like the Statute of the Artist.

M: Perhaps this is our specificity, the fact that we haven’t been hired for any exhibition. We’ve managed to charge fees, although not everywhere. Can you imagine what it would be like if we could always be hired? In this case, the preliminary work and the time dedicated to installation and maintenance would be valued and covered. And if I climb on a scaffold or injure myself during the installation of an exhibition, I would be entitled to the same conditions of protection of other hired hands such as the recognition of labour diseases or medical leave. The initiative of the statute includes specific measures in other directions, such as the income generated by copyright that is at present incompatible with a retirement pension. If instead of describing it as copyright income it is called return derived from intellectual property, it is automatically compatible. So, if it’s as easy as that, why hasn’t it been done before? The truth is that it speaks of our society, for it penalises employment income and exempts capital income, so they have to be equated. In the sphere of trade unions, it is alarming. It declares: Modification of article 3 of the organic law of union freedom that prevents self-employed workers from founding trade unions designed to protect their unique interests. We’re talking about the right to unionisation that is presumably recognised. Another proposed change: the abolition of the limit to six-month seniority in the company. Who hires the artists? Do we need to be hired in order to join the union?

A: A unitary definition of the artist is being proposed that will include museum and gallery staff, technicians, etc., because that is precisely what would give us the right to be represented by a trade union. This redefinition of the artist appears in point 1.1. of the Framework Document.

M: The specific UNION document proposes a more detailed definition: tackling the category of artist with legal criteria. That’s the interesting part, that there legally be a definition of artist that we can avail ourselves of. Legally, when do you become an artist? Today there is no legal definition, there are only criteria established as income, recognition, quality of the work, reputation, belonging to associations, self-recognition, training, conceptually the artist is also defined by lack of definition. Art’s same desire to open up and avoid being pigeonholed is at odds with the reality in which you have to adapt to a definition of artist.

A: Of course, but wasn’t this opening up, this avoidance of being pigeonholed precisely the core of art? But we’re tired of this, the Romantic artist who leads a shitty underground life for posthumous glory and all that.

M: So, what does internalising these rules mean?

A: It means leaving Romanticism to one side and immersing yourself completely in the neo-liberal machinery, but it’s the machinery that feeds you unless you don’t choose the classical ‘I do this because this is where I put my vital energy, but I’m not asking you for anything because I’m going to ask another job, teaching, to give me money …’ Doctors don’t face this dilemma, ‘I’m going to practice what I’ve studied, I practice and you pay me, then in my free time I become a supporter of naturopathy, or do voluntary work for people without resources.

M: There’s a demand for doctors, lawyers …

A: There’s no demand for artists.

M: How do we fix this?

A: The nicest part is that we insist on being the lighthouse, the light, but I wonder whether we’re not considered parasites, people who expect the state to give us a part of the taxes and scholarships available because we believe we generate a common discourse. That’s what I believe, that without culture there is no society. I think this is what is truly emancipating. In any event, if it’s real and not only propaganda it’s the maximum to which art can aspire — being able to articulate an awareness of union without turning into propaganda.

M: An awareness of union that involves individualisation and personal recognition?

A: It would involve feeling that when someone produces something, he does so for others, and that those who are closest, in his own sphere, aren’t his rivals but people who do the same thing … It’s a vision of the world in which individuals want to be together. It’s a vision opposed to that of patriarchy. I see individualisation or personal marks linked to precariousness, flexibleness, to the fact of being one’s own boss… All this, the dismantling of what we consider the modern project, is where we are now and implies that we are beginning to abandon all those deregulated Romantic possibilities and starting to form a part of the legally defined system that we used to boycott, declaring we didn’t belong to it. It implies that it’s a sort of culmination — everything has gradually passed away, it’s been left behind, and now we want to be paid like all other workers.

M: To return to artisanship.

A: Yes, because one kind of revolutionary illusion has disappeared and Santiago Sierra, for instance, rejects the National Prize for Plastic Arts, turns his rejection into a work and sells it in what is a radical stance that exposes the hypocrisy existing in art. That’s the trap — if I don’t form a part of the system, I have to accept a precarious life. The chambermaid will say she has no choice; she doesn’t form a part of this existential snobbery, which is why we have such bad press. People who militantly hate art: they talk about all sorts of things, they think they know everything but they know nothing, they give their opinion on everything, all the time, and to top it all they believe that their opinion is worth more than those of others because they see things that others can’t see. The truth is that if we look at contemporary art from the outside, to a certain extent we could consider ourselves a snobbish elite with this duality. This is where our exceptionality lies, although I’m not sure whether this speaks badly of us. When we speak of leaving precariousness behind, of the professional, fiscal and social recognition of our work, are we really thinking in terms of the Statute of the Artist?

M: When I was talking about making underground work visible I meant putting it on a par with the caring work carried out by women. The motivation is the same, love, because we devote ourselves to caring for others and with this leverage things aren’t counted or paid for. I remember a publication in which Mireia Sallarés quoted Mari Luz Esteban: ‘We defend love as an alternative to conflicts and inequalities that are perhaps precisely being nourished by love. Even today, the more a woman looks after someone, the more she is contributing to her own economic impoverishment and to her lack of social recognition.’ Love as a trap. This places us in a cruel dilemma when the person in need of care is someone very close. But defending art in this same way actually seems to contribute to the impoverishment. I think these claims can be equated, because there is a commitment and care that support and advance artistic projects.

A: Do we want asocial recognition?

M: Yes, I think so. Perhaps not a recognition, but an acceptance or normalisation. Recognition includes something more —being seen and being valued. It would just be a question of observing that we’re here and that this is what we do, not as an added value but as a way of normalising the presence and the role of artists.

A: Normalising something that aspired to not being normalised, that was militant and proud of it, that considered that this was its stance, to dissent from the norm.

M: Perhaps the problem lies in our professionalism.

A: We described professionalism as good practice, i.e., basically knowing what we’re doing. Legitimately knowing what we’re doing and doing it right.

M: But that’s with regard to others, with regard to the law.

A: Within common rulesthat validate it.

M: It’s a question of form. If the form facilitates our activity, then professionalism is positive.

A: And all the implications it has at a regulatory or normative level could perhaps be killing the spirit of artistic activity, imagining possibilities that don’t actually exist, breaking the rules. Working to break the rules and wanting to form a part of them.

M: It’s a question of fitting a definition. It’s not about limiting contents in order to stop protesting, breaking or challenging but rather to improve, to have better tools. If you have means, you have the possibility of working better. Perhaps the lack of resources can sharpen our wits, but in the long run working without means becomes tiresome and kills creativity, preventing us from growing and developing. If it leads to contradictions or hypocrisy, then art will change; if conditions change, then art will change. The perception that the artist isn’t a professional conditions our practice. At the same time, the certainty that it is more than a job keeps us on edge and on the edge.

A: Nothing has ever got anywhere without a dose of idealism. It’s impossible, it’s a question of preserving the system. The risk at a personal level is assumed by artists, whose contribution at a social level leads in part to all the rest. And they find themselves arguing for a document of minimum requirements.

M: Everything ends up being a question of authorship. If I become a messenger and a defender of an idea, it’s my idea. If I make a profit from it, it’s even more mine. On the other hand, from the position of the collectivity, if I put forth an idea to help improve society and this then happens, it should be sufficient motivation and objective. The reward for our contribution to the collectivity isn’t feasible because it obviously doesn’t help us preserve our practice in material terms. But this idealism also involves our well-being when we make a contribution or believe that what we contribute has its importance.

A: So then it’s already an act of mysticism, we’re now in the realm ofsacrifice.

M: But we can’t bring it only halfway down to earth.

A: What you’re saying sounds a bit like it’s a question of all or nothing. It can’t be half-hearted — it’s like a personal commitment to the ultimate consequences.

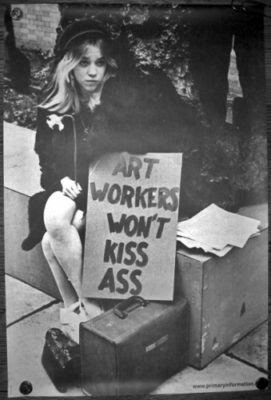

Judy Chicago addresses to the volunteers at the studio. The Dinner Party , c. 1978. Photo: Amy Meadow

Alba Mayol Curci is an artist and philologist. She investigates peripheral narratives in which emotional mechanisms can function as an activism.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)