Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Windows and More Windows

We live attached to techno-neuronal terminals that connect us to endless images, as if we had insect ommatidia that create thousands of partial images, waiting for our brain to miraculously synthesize all this information. Many of these images that circulate in the info-sphere are not created by humans but rather by machines, with no intention other than to capture what is in front of them. The filmmaker and theorist Harun Farocki was one of the first to speak about operative images and subjective phantom images (or phantom shots), images that are not made to entertain or to inform, that do not reproduce anything, with neutral, zombie points of view, with no other perspective than that of being the result of a simple technical operation. They are images from micro-cameras located in missiles that provide the perspective of a drone, images from video surveillance cameras, images from webcams that stream all day and night, images from thermal cameras at security checkpoints in airports.

All this is part of the base of the multiscreen universe, of the hyper-ubiquitous image in the Internet age, what some have called the Global Screen, Screen State or Screencracia for a tele-democracy, whose objective is, according to Fito Rodríguez, “the reconstruction of the phenomenology of seeing, of those phenomenological aspects linked to specific architectural spaces, bringing technology to an expanded concept of Bentham’s panopticon.” Both in the panopticon and in these multi-screen audiovisual spaces, visibility becomes a trap. The permanent connection and the unlimited abundance of images are two central myths through which we communicate, make love, vent our frustrations and create for ourselves an image of the world.

With the coronavirus pandemic, the multiscreen connection increased, and the interface became both a filter and a window to the world. Locked up in our homes, the digital windows were the only anchoring space to a collapsed reality that had relegated its scant vital signs to digital media. We are witnessing the collective coming of the “new normality” that involves video-connecting through virtual environments of large technology companies (Google, which went from Gsuite to Gworkspace, Microsoft which is now Microsoft 365, and Facebook which is now Meta). These are multiscreen and multitasking interfaces where communication focuses more on noise, on the inability to communicate and on what months later analysts called the syndrome of “Zoom fatigue.” The connective replaced the conjunctive (exactly as described by the philosopher Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi just before the pandemic), and the rooms themselves became pure syntax, with my face and the faces of others becoming just another element in the concatenation of (not always meaningful) signifiers, as in those “call centers” described by Mark Fisher in which tasks can be performed without thinking.

The City and the Soft Montage

Urban life has familiarized us with the split screen since we were young kids. Our own rooms are the theater of the voyeur across the street, while the buildings opposite ours show a grid or summation of split screens of domestic interiors in which we read, from our rear window, an endless system of relationships and visual combinations. In fact, in The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft, the insightful essayist Anne Friedberg reveals how we are surrounded by windows that mediate our relationship with the world, from the window of our house to the computer screen. Friedberg wrote her book one year before the appearance of smartphones and shortly after the appearance of Facebook and Twitter, anticipating the audiovisual surplus that these social platforms have generated. According to her, the space of the computer screen has more to do with the surface of cubist frontality, with the suppression of depth, with the superposition of layers, than with the Renaissance perspective. It also has more to do with the viewer as editor, something that had already happened with television zapping.

Germaine Dulac, La souriante Madame Beudet (1923)

Friedberg reminds us that the multiple screen started with the split-screen of early cinema (Edison, Edwin S. Porter) to create a special effect, the juxtaposition of two different shots in the same frame. Some of these referred to protagonists’ dreams (The Queen of Spades in 1916 by Protazanov, La souriante Madame Beudet in 1923 by Germaine Dulac, Twilight of a Woman’s Soul in 1913 by Yevgeni Bauer, Dream of a Rarebit Fiend in 1906 by the Edison company inspired by the Winsor McCay comic), or flights (Cupid’s Prank in 1908 by James Searle Dawley), etc. It was also used to force a narrative point of view that included the reverse-angle or the outside the screen shot, or for allowing the spectator to see parallel actions, as in the films Santa Claus (1898) by George Albert Smith, Suspense (1913) by Lois Weber or, later, Carrie (1977) and Sisters (1973) by Brian de Palma, among others. Another use of the split screen has to do with the emotional and/or physical distance between characters: Rock Hudson and Doris Day in Pillow Talk (1959) by Michael Gordon, Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in Indiscreet (1958) by Stanley Donen, or Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal in Rob Reiner’s When Harry Met Sally (1989). In other cases, it seems to fulfill more of a video-game function, as in films like Kill Bill (2003) by Tarantino, inherited from uses of the multiscreen by Warhol and Nam June Paik. It can also be used as a scenic element or for visual expansion, as for example in the installation of seven giant screens that Charles and Ray Eames created at the National Exhibition in 1959 and which showed the wonders of North American culture in 2,200 images. But the split screen can also be an exercise in breaking with the referential illusion, a desire to turn the screen into a mental space, a neuro-space, like the Think device that the Eames made for the IBM Fair in 1964.

Charles & Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen Associates, Model for the IBM Pavillion, IBM Fair 1964

Beyond these uses, the split screen is remarkable as a visual rhetorical figure that exercises an analytical function that inspires association, dialectics and reflection. The split screen subverts the laws of perspective by including the reverse-angle or the outside of the screen shot within the frame of the screen. The split screen presents, in an unnatural way, the simultaneity of two points of view and creates a relational, non-exclusive, non-consensual duality, with analysis dominating synthesis. The screen becomes a dialectical zone, an intertextual space, a mosaic, diptych or triptych. Meaning becomes tense in the interstice between images and the montage itself, which, according to the filmmaker Harun Farocki, transforms colloquial language into written language, and babbling into rhetoric. Alexander Kluge said: “Let us think of an image, suppose Mnyemosyne, and then another, a painting, Melancholy. In the middle, since it is impossible to unite the images, is a hollow space and in that hollow space a third invisible image emerges, which is what is real.” But the meaning also appears from the collision of the elements within the frame. The split screen is the essential way to establish a dialectical process of images, a zapping that allows us to see two images simultaneously, breaking with the human physiological limitations that allow us to see only one image in a given place and time. The split screen is a montage within the frame, what Harun Farocki called a “soft montage.”

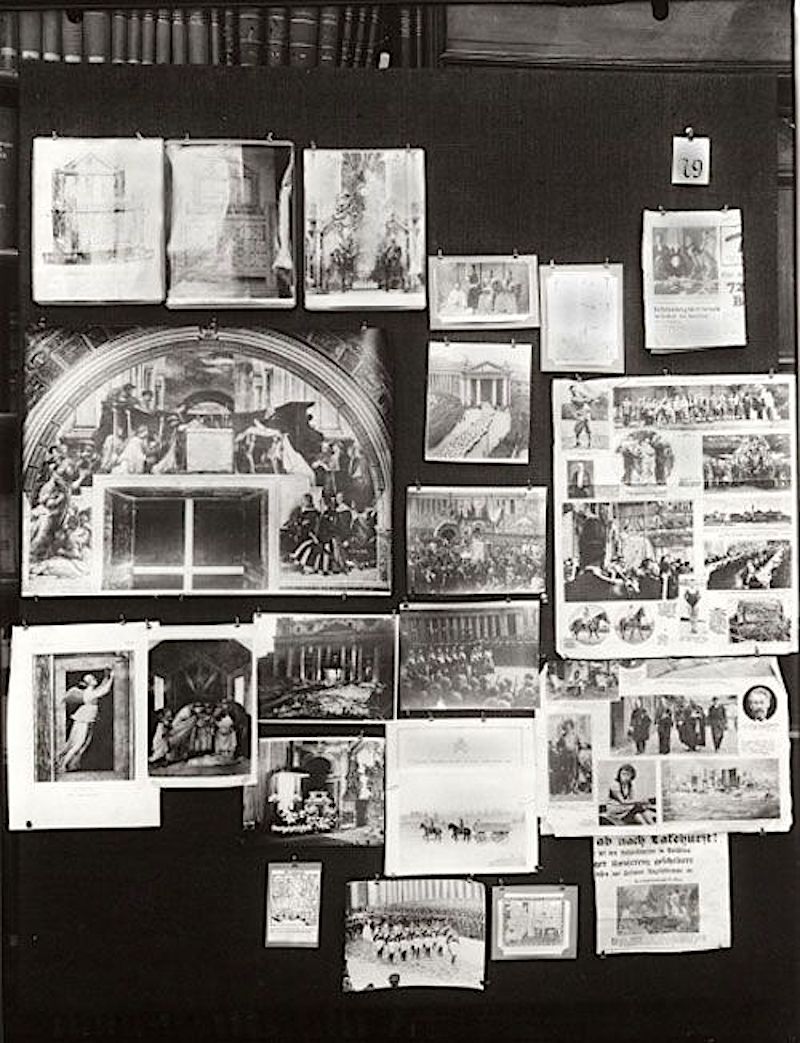

Aby Warburg, Atlas Mnemosyne

Harun Farocki and the Critical Dialectic

Farocki uses the split screen to establish a process of critical dialectics. This simultaneous perception of images is, in truth, a dialectical process that allows us to see the official images that most of us carry inscribed in our imaginations mortgaged by the media and its dissemination (cable, DTT, theaters, ceilings and walls of cities, shops and mailboxes, the Internet), and at the same time it is the reverse-angle or outside of the screen shot of the subaltern images that give another version of the events. Sometimes, the image that acts as a reverse-angle shot allows us to see how we see, showing how we receive and react to these images, how they affect us. One of the main themes of Harun Farocki’s work is what Antonio Weinrichter calls “the new economy of images, the functions it fulfills and who it serves,” which led Farocki to a comprehensive analysis of disciplinary societies and the alienating control promoted by vision and simulation machines.

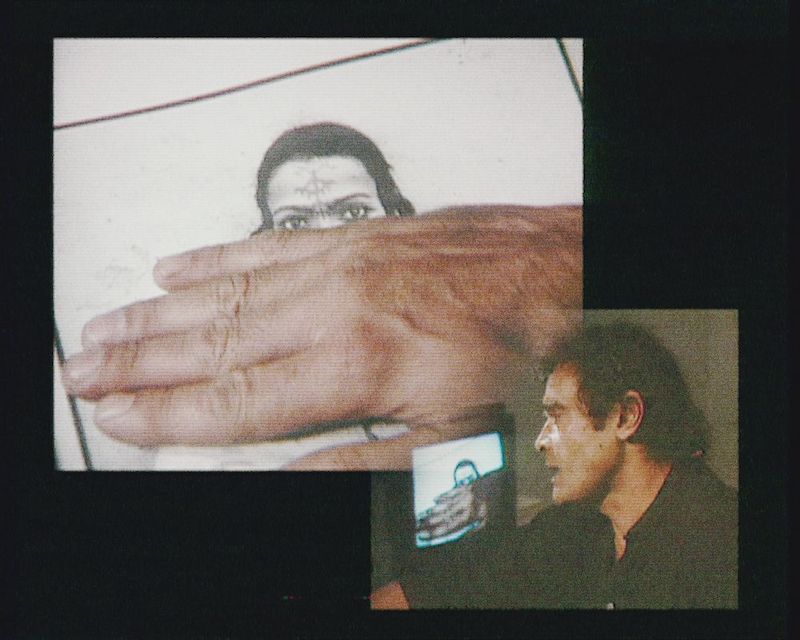

Harun Farocki, Schnittstelle/Interface (1995)

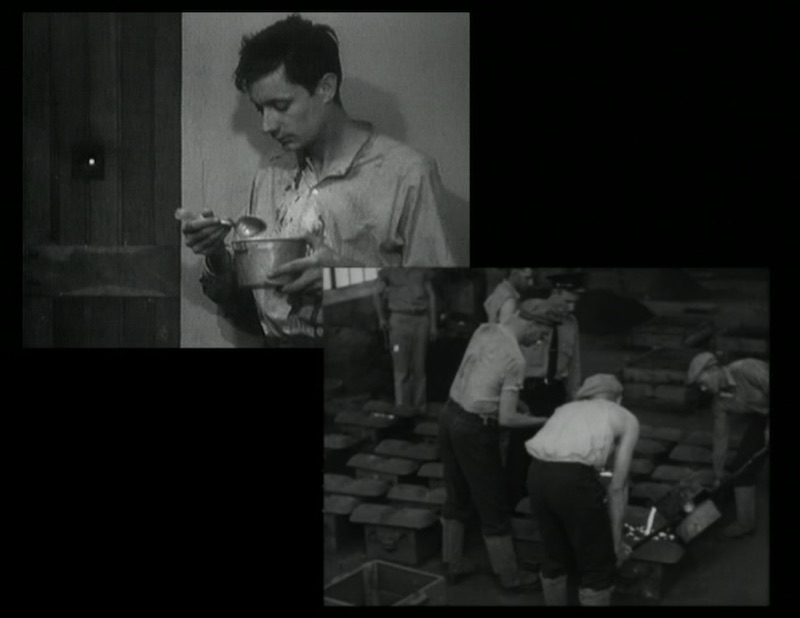

Harun Farocki, Contre-Chant (2005)

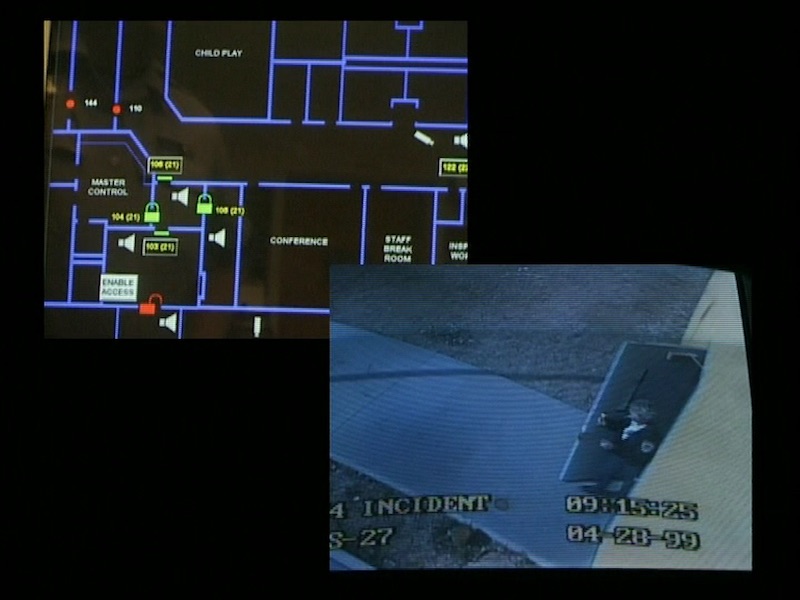

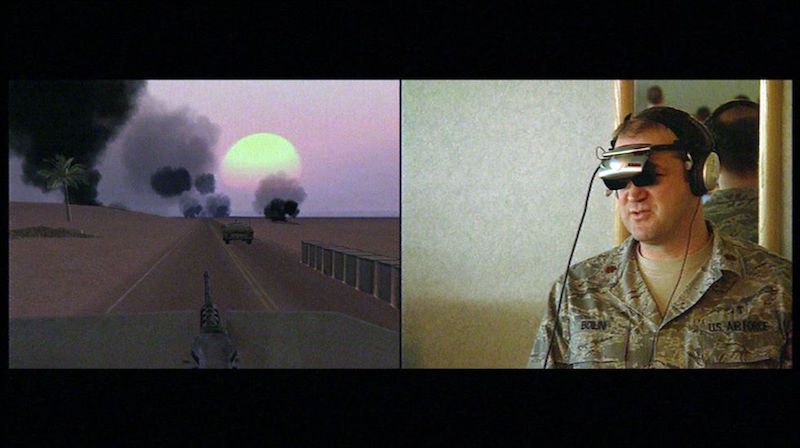

Farocki put soft montage into play in Schnittstelle (Interface, 1995), a commission from the Lille Museum of Modern Art in which Farocki is seen in his editing room reflecting on images (from his own to images of Ceaucescu) and on the relationship established between them when they are placed within the same interface. As George Didi-Huberman says, Farocki, like Adorno or Warburg, is obsessed with a dialectic that includes the entire tragedy of culture, and is concerned with the dialectic of destructive reason that allows him to see how the production of images participates in the general destruction of human beings. In Contre-Chant (2005), Farocki uses the split screen to meditate, once again, on the status of images, and juxtaposes The Man with the Camera (1929) by Dziga Vertov, industrial archives and video surveillance cameras. By means of an archeology of archives, he produces an essay on the relationships between human vision, technical vision, the human body and production machines. If in Vertov the machine was an extension of the human body, the body in the era of video surveillance cameras becomes an extension of the machines themselves, of their control. He developed this idea in Gefängnisbilder (Prison Images, 2000) and in Ich Glaubte Gefangene Zu Sehen (I Thought I Was Seeing Convicts, 2000) with images from video surveillance cameras of prisons, including those that captured the death of William Martínez in Corcoran Prison in California. In Ernste Spiele (Serious Games, 2009), the US military uses the same interactive and immersive computational animations to prepare soldiers to go to war as well as for post-traumatic therapy when they return home after the war, within the Full Spectrum Warrior program of the Institute for Creative Technologies at the University of Southern California. Farocki turns the neuro-nervous terminals into a political space and confronts the optic nerve with political muscle in that space of techno-political trompe l’oeil where we lose our autonomy and become information, control subjects in the hyperactive eyes of remote surveillance cameras.

Harun Farocki, Gefängnisbilder/Prison Images (2000)

Harun Farocki, Ich Glaubte Gefangene Zu Sehen/I Thought I Was Seeing Convicts (2000)

Harun Farocki, Ernste Spiele/Serious Games (2009)

Note: some of the initial ideas in this article are inspired by “The Eye and the Knife: An Essay on the World as an Interface” (Arcadia, 2019).

(Cover image: Nathalie Bookchin, filmstill from la Virreina exhibition)

Ingrid Guardiola holds a PhD in Humanities from the Pompeu Fabra University, is a professor at the University of Girona, essayist, audiovisual producer and cultural researcher. Since May 2021, she is the director of Bòlit – Centre d’Art Contemporani de Girona. Her work explores the socio-cultural relationships established between culture, technology and society, and focuses on issues such as inequality and gender.

@ingridguardiola

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)