Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

vis.; V; Lubricán. There is a recurrent something in some of Julia Spinola’s latest exhibition titles. A sort of invitation to synthesis, a state in which, from hints, it is difficult to clearly identify what we read or see. In vis (Espai 13, Fundació Miró, Barcelona, 2020), this shorthand for visual is referred to as if it, incomplete, in process, wouldn’t be enough to apprehend reality. In V (Heinrich Ehrhard, Madrid, 2019) a single letter could entail the beginning of a word —maybe a preliminary exercise for vis.?— and in Lubricán (CA2M, Móstoles, 2017) it was about a compound word, from two nouns, lupus “wolf” and canis “dog”, a term (in Spanish) which was used to define the transition from day into the night and from night into day, that moment in which actually images become distorted, lose stability and, once again, they’re not enough to distinguish and apprehend reality.

vis., curated by Marc Navarro Fornós, is the third exhibition in the Gira tot gira cycle for the 2019-2021 season of Espai 13, at the Fundació Miró. It follows the project by Laia Estruch and Beatriz Olabarrieta, this one with a sobriety, chromatism and dismissal of showiness which leads very fittingly into Julia Spinola’s exhibition. It will be followed soon with Lorea Alfaro’s and Jon Otamendi’s project, who will conclude the cycle in spring.

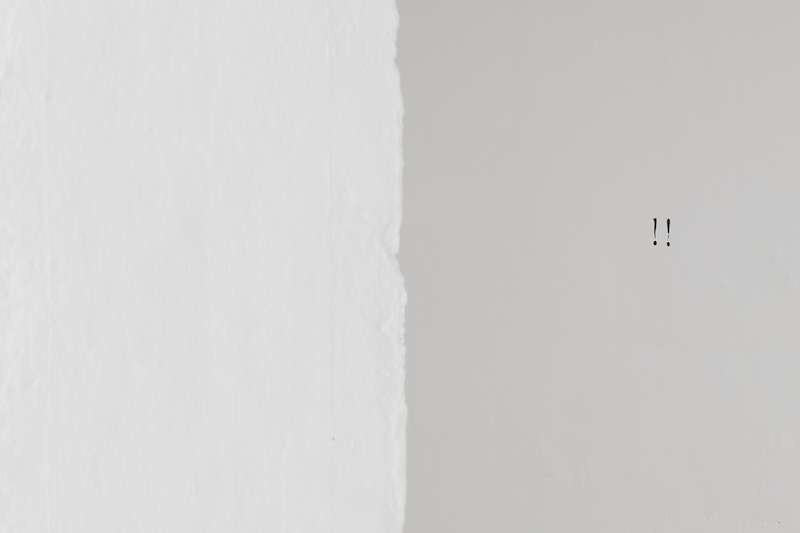

Visiting vis, after descending the staircase leading up to the exhibiting space, we find a seemingly empty room in which all pieces, sculptures and drawings are to be found in the margins, always next to one of the walls. Movement is free and limited at the same time. I found myself, occasionally, right in the centre of the room, rotating around myself so I could observe everything about me. Then, stuck against the wall so I could manage to see some details of those pieces. Impossible to circle entirely, cardboard sculptures are either supported or suspended on each of those walls, being, on any side, unreachable, and bringing to the fore matters of tension, weight, lightness or resistance. These are a series of sculptures which are variations on a single principle, cardboard tubes which occasionally are the product of bringing a number of pieces together – the points of attachment are visible, even highlighted. In the same way titles are partial, unfinished, Spinola’s oeuvre is left unfinished. It’s displayed as if it were a sketch which literally —you’d run into the wall— is never quite going to be finished.

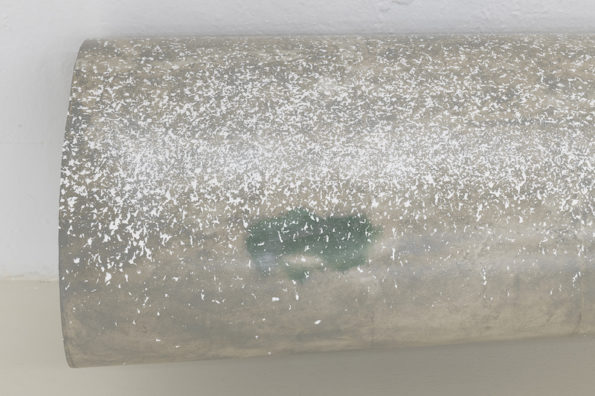

Alienation, the focal point of the Gira tot gira cycle, of which this cycle is part of, as well as tricks or likely deceit or limitations to our perception abilities is visible here. The three sculptures are supported – pointing at a relative stability – in different ways, which exerts an apparent effect on the shapes which they take and which, in a subtle manner, make one different from each other. One of them, the one which keeps in a more intact way the tube shape, is suspended by two ribbons surrounding it, a few centimetres from the ground. The other one, resting on the floor and against the wall, has its two ends joined, as if it had decided to withdraw into itself to avoid rolling on the surface. At the same time, out of the three, this is the one in which the notion of remnant is more present, as if, in order to take that shape, it would have needed to add and assemble cardboard pieces to cover the possible flawed and broken pieces created by manipulating and overstraining the material’s shape. The third sculpture is supported by three rods which come out of the wall, also a few centimetres from the floor. Once again, the three points of support produce an indentation so the ends lean towards the floor. A “deformation” which I don’t know if it’s produced by the support or if it has been previously made on purpose.

In the continuous transaction between bidimensional and three-dimensional in Spinola’s oeuvre a series of drawings are also part of the exhibition. They are small-scale screen printing inscriptions, scattered around the several walls of the room, engaging a dialogue of sorts with the sculptures. The graphic pieces establish some patterns which, sometimes, show the inflection points or attract our attention explicitly, and, elsewhere, are reminding of some textures and stains we can find on the sculpture’s surface. The ensemble of elements, sculptures and drawings is constructed as a fabric on which some gestures are chained together.

Spinola has occasionally indicated she works from a particular binarism: association of ideas, images or shapes. I remember, during our wander at Lubricán in 2017, how she mentioned precise words such as “shell” or “sand” as we strolled among the pieces. Starting points which allowed her, somehow, to start a process, to transform matter from a reference which, as a result, ended up vanishing. It’s possible that the visitor won’t find that starting point clearly if they don’t know the words, but it’s extremely thought-provoking and even visible when the artist explains the process. This time she has worked with shapes inspired by the organic world: “horn” and “limpet” are two of the words mentioned in the opening text. We might as well imagine the limpet in the sculptures clinging to the walls, which hides one of its sides and blurring its outline in its environment.

As on other occasions, there is a particular idea of raw reality to be found in the artist’s concept. A raw reality which is displayed in the brown colour associated with primitive motherhood, where matter’s physical presence and its transformation and molding ranks above narrative, until you stumble upon those images and ideas which have served as starting points and allow “word and matter to come into contact”[1].

[1] Herráez, Beatriz. “Lubricán o de cómo ‘meterse en un jardín’” en Lubricán. Julia Spínola, Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Móstoles, Madrid, 2017.

Marta Sesé researches and writes abour contemporary art. She lives in Madrid and works in arts publishing. She also co-manages the project Higo Mental: www.higomental.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)