Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

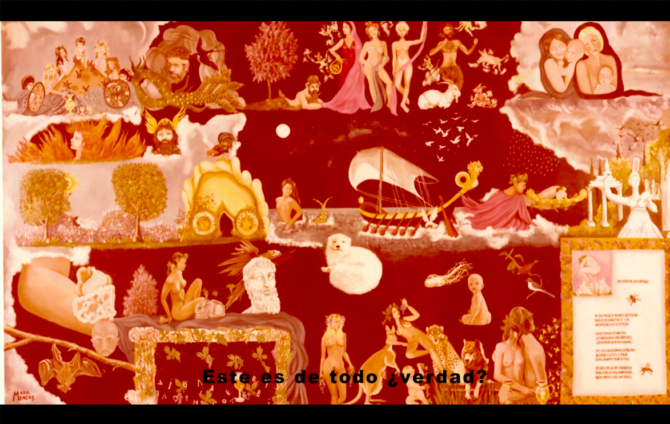

‘We liked the house because apart from its spaciousness and antiquity (today old houses succumbed to the most advantageous sale of their materials) it kept the memories of our great grandparents, our paternal grandfather, parents and our childhood.’ As you know, Casa tomada is a short story by Julio Cortázar in which two brothers, confirmed bachelors and idle (‘We did not need to earn a living; every month money arrived from the farms and the money increased’), are gradually dispossessed of the rooms in their house due to an unnamed invasion. ‘They have taken over the back part.’ Even though the association isn’t direct, I remembered this story when I saw some excerpts from Tres hermanas, the documentary that film maker Blanca Bonet will release in the next few months. The sisters in question are great aunts of Bonet’s, single and nonagenarians, who have spent their entire lives shut up in a ramshackle Sevillian house making art. The film is quite unique: one of them copies on huge tapestries works from the Renaissance they have seen on slides (they have a very complete album, like those used to teach Art History, with which they learnt to paint, copying projections of works by old masters; they take the slides out and look at them, as if they were relics). She also makes many portraits of bullfighters. Another one copies famous pictures, replacing the characters with cats. The third one paints in a surprisingly contemporary fashion, yet, to make up for it, she lives with her stuffed dog.

Marginal practices can appear in the most unexpected of places, even in a bright ramshackle Sevillian house. This has its dangers, because the surroundings could prove confusing and we could consider what is done out of necessity – almost for survival – as a distraction. It’s not surprising that well-bred ladies should amuse themselves painting little pictures. Since the age of Romanticism, art has been an aristocratic diversion: a leisurely form of work, subject to exceptional mechanisms of production because, although it’s made with the hands, it appears to be made with the spirit. Spending a while in the studio every morning, without the troubles of the art trade – selling works, living in hardship, fighting with dealers, critics and similar queer fish, etc. – because one is well off is a happy pastime that involves no risk. Painting like Cayetana de Alba painted. Moreover, what could be more bourgeois or distinguished than having one’s house full of paintings, busts of Roman emperors or rock crystal glasses?

Yet the case of the Mencos sisters is surprising, because all they’ve ever done is live in that house and create that work (self-absorbed people are always fascinating). Decoration is a subliminal process of spatial domestication, the mechanism through which a foreign place becomes one’s own. We mustn’t forget the context: when the sisters were sowing their wild oats, women didn’t ‘leave home’ but changed her father’s home for her husband’s (here spintsterhood has a topographical nuance). The construction of subjectivity has its difficulties under these conditions: if escaping from marriage allows them to operate with a certain autonomy, inhabiting the family house obliges them to accept a space and belongings that are as strange as they are familiar. The three sisters have upholstered the house from top to bottom, and although what each of them does is different, everything fulfils the same purpose: appropriating themselves of the space, protecting themselves, not only from the influence of their ancestors but also from the influence of each of the other two. Somehow, the work of each sister delimits the area of its creator and gives it its distinctive shape. There is extravagant proof of this: one of them has disguised her bedroom door by making it look like a library. As is well known, all houses that take pride in themselves must have a secret door.

A comment on the works. It is often said, particularly in the field of visual studies (the unneeded multiplication of disciplines), that art produces images, in spite of the fact that over the centuries it has produced objects in abundance. Artistic objects, furthermore, are highly desirable and one would like to take them home, possess them and live with them. It’s difficult to buy The Birth of Spring, but it can be copied from a slide, not in order to learn about Botticelli (in the sense in which technique is practiced copying the old masters) but to take possession of the work and hang it over the settee. The discredit of the reproduction is deftly compensated by the aureole of the work itself, distinctly emphasised when tempera is replaced by fabric, or the head of Charles IV by that of a pussycat. This relationship with masterpieces could be interpreted lightly as a trivialisation of the original and its aura, when in fact it’s exactly the opposite: it isn’t the image of the work that is desired but the work itself, and before the impossibility of obtaining it, a simulacrum is set up. Leafing through the slide catalogue, they read a list of coveted objects that they can acquirewith their ingenious method. ‘I visited the museum a lot and I always went to see that one. I don’t know why, but there’s something about that painting … that makes you adore it. That sort of thing is adorable’. The copies were so eccentric that they couldn’t be accused of fraud (they didn’t run the risk of anyone believing that the wool was being pulled over their eyes) and enabled them to live in a museum of their own, among Botticellis, Van Eycks and Goyas. ‘This one’s mine,’ she says, pointing to the slide.

At the same time, all this follows a logic of personal assertion. In his lecture on blindness (an edited version of which appeared in Siete noches, of 1980), after describing his ‘modest personal blindness’, Borges began to recite a long list of illustrious blind men: Homer, Milton, Groussac, Joyce. Thank to this artifice he attributed himself an illustrious lineage as the descendant of distant, prodigious blind men. Those who remake the works of the old masters can safely say that they are artists, not mere copyists.

The house of the Mencos sisters has specific conditions that arouse my curiosity, to say the least. They have channelled the problems of seclusion and idleness into what is quite a unique form of art production, displayed seldom though always in picturesque places (palatial houses and similar venues). Blanca Bonet told me that at first they would paint on walls, and Miró’s atelier in Palma, abundantly daubed in paint, sprang to mind. This is a very intimate practice, almost a sanctifying gesture, as when the altars and walls of a temple are anointed. I believe the Mencos sisters understand art as a practice of resistance, behind which they can seek refuge from the intrusions of the world: wedlock, offspring, social life, etc. So, seen from this angle, all this delirious and marginal work is connected to one of the great motivations in art history.

Their lustrous lineage doesn’t derive from their copying of old masters or from their Andalusian nobility, but from their perhaps unwitting endorsement of what we could describe as the romantic idea of practicing art as an intimate act of resistance. If we had to pinpoint a single quality among this crazy – and to a certain extent decadent – production, I think this would be it.

Captions: Still from the documentary in preparation entitled Three Sisters. Courtesy: Blanca Bonet.

Joaquín Jesús Sánchez (Seville, 1990) is an art critic, writer and freelance curator. A graduate in Philosophy and holder of an MA in the History of Contemporary Art and Visual Culture, he contributes to prestigious publications, both in Spain and abroad, and in other lesser known sources. Besides researching compelling and complex subjects, he devotes much of his time to trying to memorise Borges’s oeuvre and is fascinated by gastronomic literature. You can follow his exciting adventures at www.unmaletinmarron.com.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)