Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The relationship between historical chronology and order is unavoidable. Where there is enumeration there is order, where there are great events there is chronology, succession and history.

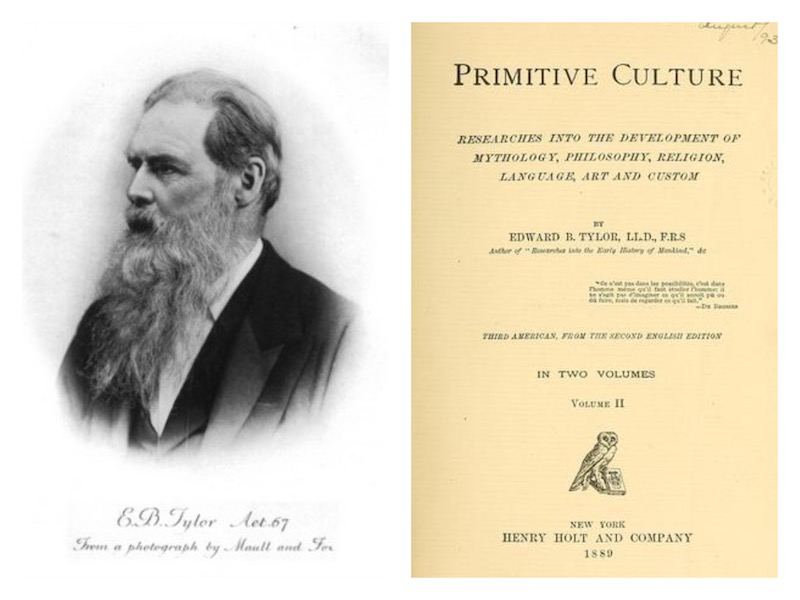

Anthropology, in its beginnings, enjoyed the scientific authority to be able to name time. Distinguishing between real timeand factual timewas its task. Well-meaning early anthropologists extended the idea of multiple chronologies: dominant and subordinate. An advanced culture coexisted in factual time with a backward culture, but never in real time. Pitt-Rivers, the creator of the famous Oxford Ethnographic Museum, stated that “the existing races, in their respective stages of progress, faithfully represent the races of antiquity.” The study of a fossilizedor primitive culture, one which had remained stuck in time, illuminated the past.

“The location of time, the place where time mattered, was the West.”[1]Moxey, K. El tiempo de lo visual. La imagen en la historia. (Visual Time. The Image in History). Sans Soleil, Barcelona, 2015, p. 25..

**

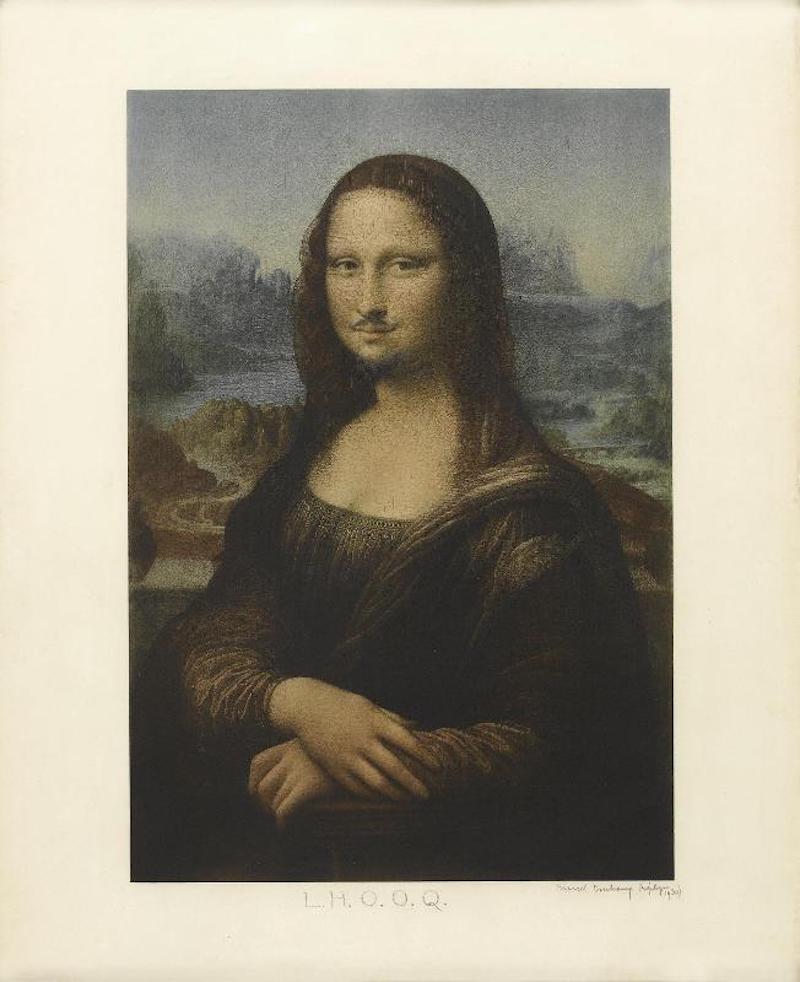

I was six years old when that famous novel by Dan Brown was published. With childlike innocence I lived through the rise of the new pictorial mysticism, which turned Mona Lisa’s gaze into a strong market artifact. When I asked adults why that portrait was so important, they told me that it was the only painting that followed you with its eyes. They couldn’t give me any more clues. When I traveled to Paris as an adult, I would see for myself. This is how the anachronistic gaze develops.

In 1620, Francisco Ribalta paints Saint Francis of Assisi embracing the recently-crucified Christ. In this pictorial exercise, devout figurative speculation, an anachronistic power modelled by the sensation of unreality is revealed: over twelve centuries separate the birth of Saint Francis from the death of Christ.

For Jacques le Goff, the main pictorial mutation of the Middle Ages occurs when people become aware of time. According to his thesis, there comes a time when the portrait is emancipated from the desire for eternity and shows subjects in their ephemeral being[3]Le Goff, J. (2020) Por otra Edad Media. Tiempo, trabajo y cultura en Occidente. (Time, Work, & Culture in the Middle Ages, 2020). Madrid: Taurus, p. 68.. The contemporary twist, which Walid Raad represents so well, shows us temporality added to a work of art. It is no longer a question of conceiving it as a thing, but as an object.

If relating images is the impetus of curating, if in order to think about images one must put them in relation, then anachronism is not something exceptional, but rather the ground on which one works, something common and established. Why still talk about the meaning of time? It is not a question, in this special issue on heterodox temporalities, of justifying subordinate forms of constructing history(s), nor of insisting on how a work of art is capable of breaking temporal limits. It is about continuing to open the question, as Patricia Lara Folch does within dance, thinking of the temporary inscription of the gesture as something political, or like Juan Gallego Benot does when reflecting on the object framework that Walid Raad builds within an institution that is supposed to be ‘temporarily closed.’ It is a matter of entering, like Manu Padín, into a territory where time is suspended, and to start thinking, in images, in terms of that place.

| ↑1 | Moxey, K. El tiempo de lo visual. La imagen en la historia. (Visual Time. The Image in History). Sans Soleil, Barcelona, 2015, p. 25. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | https://elpais.com/diario/2002/06/29/babelia/1025305567_850215.html |

| ↑3 | Le Goff, J. (2020) Por otra Edad Media. Tiempo, trabajo y cultura en Occidente. (Time, Work, & Culture in the Middle Ages, 2020). Madrid: Taurus, p. 68. |

Pablo Caldera (Madrid, 1997) is a PhD student in Artistic, Literary and Cultural Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. A graduate in Philosophy, he combines academic writing with narrative and visual arts criticism.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)